by

J. Eric Gentry, PhD, LMHC

Amy Menna, LMHC, CAP

Marjie Scofield, MSW

APRIL 1, 2004

TRAUMA ADDICTION: SAFETY AND STABILIZATION

Erica is an attractive, 30-year-old woman who recently completed a 28-day recovery program for substance abuse. Erica is a survivor of childhood abuse and has experienced sexual trauma as an adult. She has been in and out of therapy for years with a variety of therapists. She began using alcohol in her mid-teens as a way of coping with her feelings. Her use progressed as she became older and she eventually began to abuse prescription drugs as an adult. When Erica was in her late-twenties, she was raped in a park while jogging. Shortly after the rape, Erica’s substance abuse intensified dramatically as this became her primary way of managing her fear, anxiety, nightmares, and the disturbing childhood memories that began to surface.

As she brushes her teeth this morning, she notices the color in her face. Today she is able to look in the mirror with a sense of self-respect knowing that she is recovering from the deadly disease of addiction which she has been struggling with for years. With newfound confidence and gratitude, she gets ready for work looking forward to the day ahead.

Her neighbor, Brad, is a teller at the bank with Erica. A few months ago he was severely beaten while attempting to purchase drugs in a dangerous neighborhood. The terror he felt during the beating and the subsequent consequences became a “bottom” for Brad. He began attending Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings and has been drug-free for two months now. This morning Brad wakes up from having a dream about the night he was severely beaten. He has dreamt about how they robbed him of the large amount of money and how the assailants continued to beat him. He also dreamt of using cocaine again-a relapse. Just yesterday he was talking to his therapist about how these “using” dreams had nearly ceased. Last night’s was the first he has experienced in over a month and he is relieved that they are becoming rare. As he gets into his car, he feels grateful that he is not using drugs or putting himself in dangerous situations any longer.

When Brad arrives at work, he makes a quick phone call to his girlfriend before the bank doors open. She has been supportive throughout this process and has even attended some open NA meetings with him. They plan dinner tonight. At the same time, Erica makes a phone call to her sponsor with whom she has daily contact. They agree to go to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting this evening and then out for coffee.

INTRUSIVE SYMPTOMS

This morning, Brad routinely assists each customer taking deposits and distributing money. After lunch, Brad receives a large amount of cash to deposit. As he places the cash in the drawer, he starts to think about all the drugs he could buy with that amount of money. This thought has come unexpectedly and he starts to fantasize about getting high again. Brad shakes his head and thinks about the ridiculousness of this vision as he remembers the many consequences he has suffered through his drug use. He has been clean for two months now and is enjoying the budding self-esteem and hope that he is beginning to feel. He shrugs off these crazy thoughts and attributes them to the extra cup of coffee he drank this morning, which is making him jittery.

At the next counter over, Erica looks up at her next customer, believing she recognizes the beard of the man who raped her. She jumps back, but then quickly realized the customer is Mr. Martini, a longtime bank customer. Even so, she begins to feel discomforted by an encroaching fear and disturbing physical sensations. She is feeling some of the same feelings she felt during the rape and is involuntarily remembering some of the events from this trauma. She becomes so anxious that she is unable to finish the transaction and retreats to the break room. Erica feels upset and angry. She doesn’t understand why now that she is sober and supposed to be feeling healthier, she keeps having nightmares of the rape, shadowy visions of her childhood and experiences like she had today in the bank. She thinks, “These things never happened to me when I was drinking.”

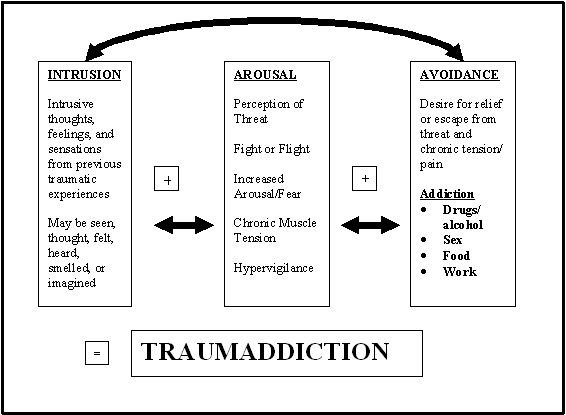

What is it that caused these two individuals to react to these normally benign experiences in ways they did not choose? How were they, in one minute, coping well in their newfound recovery and, in the next, nearly debilitated? In Brad’s situation, addiction professionals recognize these phenomena as becoming “triggered” and as “euphoric recall” which are considered relapse warning signs. Trauma specialists would identify that Erica has experienced a flashback, or intrusive symptoms, from her previous trauma. In both cases, we see how Brad and Erica react to situations in ways they did not want. Brad had no intentions in the beginning of the day to fantasize about using cocaine and Erica did not intend to becoming incapacitated by the sight of someone whose beard reminded her of the man who raped her. Prior to this, both were planning on a peaceful evening of continued recovery.

What has caused the ghosts of the past to haunt these two individuals in their early recovery? Both perceived the benign events of their day as a threat-a menace to their survival–which activated their sympathetic nervous systems, or the “fight or flight” responses. Brad’s brief inflamed desire to use drugs was challenged by his knowledge that addiction is a serious disease and that if he used again he would suffer unwanted and possibly dyer consequences. His mind perceived his desire to use drugs as a threat. As this internal struggle escalates, tension and bodily discomfort are the result. Often this tension and bodily discomfort create a desire to find relief. For a long time Brad’s primary means of attempting to accomplish this has been drug use. In the past, cocaine had temporarily cloaked his awareness of his emotional and physical pain, providing him with temporary relief from his state of internal discomfort. Now, all the tragic consequences he suffered as the result of his habitual use begin to fade into the background as the drug siren ever more loudly promises relief. He is trapped in the negative and painful quicksand of TraumAddiction.

Erica also perceives a threat when she sees the customer’s beard and involuntarily recalls her rape. When she was attacked one of the first things that she saw was the rapist’s beard. Seeing someone with a minor resemblance to the man who raped her produced thoughts and images of the rape. Even though she was perfectly safe at her job in the bank, she felt a life-or-death threat while she reexperienced the memories and sensations associated with the rape. Erica too was suffering from tension and bodily discomfort that clamors for soothing and/or escape. For years alcohol has been her most successful way of coping. Shortly after this incident, Erica begins to think that a little wine might help her feel better. She is trapped in the web of TraumAddiction.

Fig 1. TraumAddiction

AROUSAL SYMPTOMS

Brad feels anxious and decides to smokes a cigarette hoping it will calm his nerves. He can feel his heart racing and is afraid that he will have a panic attack. His lighter is not working in the wind and he becomes increasingly agitated. As he returns to work he is irritable and starts to notice his coworkers “not doing anything.” His heart rate rises and he feels pressure in his chest. There is a sinking feeling in the pit of his stomach that will not go away.

Brad, seeking someone to talk with, comes up behind Erica and taps her on his shoulder. She jumps back and turns around ready to defend herself as she was taught in self-defense class. He is annoyed by her reaction and tells her to “just relax.” Erica’s response was far more intense than she would have anticipated. Her level of arousal was high to begin with and Brad unexpectedly approaching her from behind simply put her over the edge. Erica feels that she needs a break. She, too, goes out to smoke a cigarette only she cannot hold the lighter because she is trembling. Her heart races and she takes a deep breath to calm the pounding of her chest.

Brad is experiencing a great deal of discomfort and is unable to relax. He is experiencing what is known in the addiction realm as being restless, irritable, and discontent. He is plagued by thoughts and physical urges to satisfy his craving. It is as if his insides are screaming for the temporary relief drugs can bring him. He begins to “romance” the idea of using again without a thought towards many of the negative consequences he has suffered from his drug use.

Erica continues to feel the pressure in her chest and finds it hard to take a full breath. She is constantly scanning the room as the feeling of danger lingers. With respect to trauma, these are known as arousal symptoms. Her body has become ‘on alert’ as she perceives her safety has been threatened. She finds that she is plagued with a nagging yet comforting thought that a drink would “calm her nerves.”

AVOIDANCE SYMPTOMS

Erica decides that she is too “stressed out” to continue work. She tells her boss that she is having stomach problems and needs to go home. She plans on cooking a nice dinner and then relaxing the rest of the evening. Because she has had such a difficult day, she calls her sponsor and leaves a message saying she is unable to make the AA meeting.

Brad also chooses to take the rest of the day off. He calls his girlfriend to cancel their dinner plans telling her that he is too tired. Brad cannot seem to stop his inner trembling. He is extremely agitated and continues to reminisce about the relief cocaine would provide. On the way home, he decides to go to a movie, hoping this will help distract him from his thoughts of using drugs.

Earlier this morning, both Brad and Erica had good intentions for the day. Although they had some difficulties throughout the night, they woke up with a strong commitment to recovery. Both were able to maintain their intentionality-in this case, continued recovery–throughout the morning. During the morning, both were able to direct their behaviors in ways that they wanted to behave. However, throughout the day they became reactive and began to fall victim to environmental cues (smells, thoughts, images, feelings) that provoked memories of their previous traumatic experiences. This recall of trauma, either consciously or unconsciously, produced feelings of increased arousal, fear, and muscle tension. This fear and tension involuntarily compels Brad and Erica to shift from the parasympathetic nervous system (relaxation, comfort, and intentionality) to the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight, survival, irritability, and escape).

Brad and Erica’s good intentions for the day have been thwarted. They are now experiencing such high anxiety that escape feels necessary. Both are experiencing the dissolve of their commitment to recovery as thoughts of using drugs/alcohol promise escape from the fear, irritability, and tension-they are in a reactive state. As the perceived threats and the accompanying discomfort escalate, their perceived options diminish until it feels like reckless escape is all that remains.

On the way home, Erica drives by the park where the rape had taken place. She often avoids this route as it reminds her of the rape, but today there is road construction and she has no other choice. As she unwillingly glances over at the park she thinks she smells the scent of the cologne the rapist had worn. She remembers the strong musky smell and feels as if she cannot breathe. She cannot believe this feeling of overwhelming fear is happening to her twice in one day. She feels as though she may be “going crazy”. Believing in the moment that she has no other way to survive these feelings of panic, she turns into the liquor store parking lot. She buys a bottle of her favorite wine and starts drinking it on her way home. Almost immediately she experiences a feeling of warmth throughout her body. As her body begins to relax from the effects of the alcohol, the intensity of her emotions begins to lessen.

Brad left work intending to go a movie. However, his anxiety was so high, he felt he would be unable to sit still. On a whim he decides to go for a drive and heads for the beach to relax and walk off some nervous energy. Instead, his car takes the exit to the area where he used to buy drugs. Before he knows it, he is driving down the same street where he was so violently beaten just months before. He starts to reconsider, realizing how much better his life has become since he has stopped using drugs. Suddenly he sees the alley where he was left for dead and begins to re-experience the terror he felt then. His anxiety heightens and Brad frantically scans the street for a drug dealer. All he can think about now is his desperate need for relief. He agitatedly finds his old drug dealer and purchases crack cocaine. Smoking it on the way home, he finally quiets the inner turmoil.

Both Brad and Erica find themselves again embroiled in their addiction. “How did this happen?” they both ask themselves. “What is wrong with me? I should know better. I am a hopeless failure,” become the familiar refrain of thoughts that now plague each of them. They have become hopeless, depressed, and accelerating into the desperate tailspin of TraumAddiction.

TREATMENT OF THE ADDICTED SURVIVOR OF TRAUMA

The vignettes above portray the common phenomenon of trauma leading to addiction and addiction leading to trauma. A survivor of trauma is at a significantly greater risk of developing some type of addiction and the reverse is also true. Having this awareness, it is imperative that we look at more effective ways of treating this unique condition.

The challenge of providing effective treatment and interventions for persons with both posttraumatic stress and addiction has caused many a seasoned clinician to shudder. “Dually diagnosed,” seems to rank with “Borderline Personality Disorder” as one of the more pejorative and emotionally laden labels that saddle clients. Addicted survivors of trauma are often the recipients of the anger, frustration, and trepidation of health care workers due to the difficulty in both conceptualizing and administering effective treatment to this population.

Sullivan & Evans (1995) describe the trajectory of treatment and recovery for an addicted survivor or trauma as one fraught with potential pitfalls and disappointment for the clinician. They discuss a process frequently experienced within this population as they begin their treatment/recovery. It seems as addicted survivors begin to gain periods of abstinence from chemicals (or behaviors) upon which they have been dependent, they find the intrusion, avoidance and arousal symptoms of their traumatic stress becoming more florid. Conversely, to compound this conundrum, as the addicted survivor becomes ready to begin the process of resolving the traumatic material, they often find themselves with elevated and irresistible cravings for their drug or addictive behavior of choice.

So, what constitutes safe and effective treatment for the addicted survivor of trauma? A few writer/clinicians have tackled this question and we recommend reading the excellent works of Sullivan and Evans (1995), Miller and Guidry (2001) and Dayton (2001). Each of these popular texts is written for clinicians but may be easily read and understood by survivors.

Sullivan and Evan (1995) discuss the impact of abuse and the absence of safety in their book Treating Addicted Survivors of Trauma. This book gives an excellent overview of the effects of abuse and trauma suggesting that the missing element is safety. Addictive behaviors are framed as “unsafe behaviors” which need to be worked through vs. punished (i.e. discharged immediately from treatment). In their book, they also provide an overview of interventions to assist the client in achieving and maintaining safety such as safe planning, contracts, and environmental concerns.

Tian Dayton’s book Trauma and Addiction (2000) is easy reading for a client and discusses the idea of “emotional literacy.” Dayton gives an overview of the traumatic response as well as the connection between trauma and addiction. She discusses the four stages of emotional literacy beginning with the ability to feel the fullness of the emotion. Very often trauma survivors are overwhelmed by emotions to the point where their method of coping is to dissociate. For addicted survivors of trauma, addiction is the primary method of dissociating.

She goes on to describe the remaining phases of emotional literacy as labeling the feeling, exploring the meaning and function within the self, and then making a choice to communicate it to another person. Through feeling the full sense of the emotion, one can use it as an inner guide for recovery. With a more fluid sense of one’s emotions, one is better equipped to determine whether they are safe.

SAFETY AND TRAUMA RESOLUTION

The lynch pin that connects treatment of both traumatic stress and addiction is the development and maintenance of safety and stability. Without the ability to self-rescue, one is at great risk for being overwhelmed by memories or resuming addictive behaviors. A good analogy to use for this phenomenon is the idea of firemen being trained to control fires. The first thing they learn is what to do when the fire begins to control them. Any fireman needs to know when it is time to step back from the fire in order to maintain safety and in the end, conquer vs. be conquered. The same is true with the trauma survivor. Without the ability to self-regulate their own anxiety and arousal, the trauma survivor is at risk of being overwhelmed by memories without the ability to induce a feeling of safety. At this point, the traumatic material renders the survivor once again with the feeling of entrapment, with no way to “survive” other than resuming the addictive behavior.

What is Safety?

Gentry (1996) attempts to define and operationalize the concept of “safety” into three levels, relative to the treatment of trauma survivors. These three levels of safety are as follows:

Level 1.

RESOLUTION OF IMPENDING ENVIRONMENTAL (AMBIENT, INTERPERSONAL AND INTRAPERSONAL) PHYSICAL DANGER;

Removal from “war zone” (e.g., domestic violence, combat, abuse)

Resolving active addiction

Behavioral interventions to provide maximum safety;

Address and resolve self-harm.

Level 2.

AMELIORATION OF SELF-DESTRUCTIVE THOUGHTS & BEHAVIORS

(i.e., suicidal/homicidal ideation/behavior, eating disorders, persecutory alters/ego-states, process addictions, trauma-bonding, risk-taking behaviors, isolation)

Level 3.

RESTRUCTURING VICTIM MYTHOLOGY INTO A PROACTIVE SURVIVOR IDENTITY

by development and habituation of life-affirming self-care skills (i.e., daily routines, relaxation skills, grounding/containment skills, assertiveness, secure provision of basic needs, self-parenting)

What is Safety for the Addicted Survivor

Therapists are taught from the first days of clinical training to “above all do no harm (primum non nocere),” which makes it logical to assume that the more safety and stability that we, as clinicians, can impress in the lives of our clients, the better for their treatment – right? This may not always be the case and in many instances, the clinician’s focus on safety is more about their own apprehension and may actually escalate the crisis of the client.

So, how safe do you have to be and how do you get there? Destabilization tends to be precipitated by client behaviors and thoughts in response to the bombardment of intrusive symptoms (nightmares, flashbacks, psychological and physiological reactivity). Therefore, being able to manage these symptoms safely is imperative. There are no hard and fast criteria for safety, but we will discuss various techniques to help establish safety and stabilization and discuss reference points that can be useful to help you decide. A clinician’s best intervention to optimize safety is a non-anxious presence along with an unwavering optimism for the client’s prognosis.

Firemen who only stay in the firehouse practicing what to do in the event of a fire never gain mastery over fighting fires. Clients should develop the minimum (“good enough”) level of safety and stabilization and then address and resolve the intrusive symptoms by enabling a narrative of the traumatic experience. This is often counter-intuitive and usually anxiety producing for the clinician. However, the client will be much better equipped to change his/her self-destructive patterns (e.g., addictions, eating disorders, abusive relationships) with the intrusive symptoms resolved because s/he will have much more of their faculties available for intervention on their own behalf.

MINIMUM STANDARDS OF SAFETY

1. RESOLUTION OF IMPENDING ENVIRONMENTAL (AMBIENT, INTERPERSONAL AND INTRAPERSONAL) PHYSICAL DANGER.

Level One of Safety includes the resolution of environmental danger. When treating an addicted survivor, environmental danger may manifest itself in unsafe situations such as those of domestic violence, living with an active addict or self-destructive behaviors. Traumatic memories will not resolve if the client is in active danger.

Active addiction IS active danger. The addicted survivor must arrest active addiction before treatment for recovery to be effective. This needs be clearly communicated to the addicted survivor and may be articulated as: “Safety is the requirement for resolving both your addiction and your traumatic stress. This safety will require that you bring your using behavior under control (i.e., abstinence) and that you develop ways of effectively regulating your own anxiety, without the use of chemicals or self-destructive behaviors.”

2. ABILITY TO DISTINGUISH BETWEEN “AM SAFE” VERSUS “FEEL SAFE.”

Many trauma survivors feel as if danger is always lurking around every corner. In fact, the symptom cluster of “Arousal” is mostly about this phenomenon. It is important for the clinician to confront this distortion and help the client to distinguish, objectively, between “outside danger” and “inside danger.” Outside danger, or a “real” environmental threat, must be met with behavioral interventions designed to help the survivor remove or protect her/himself from this danger. Inside danger, or the fear resultant from intrusive symptoms of past traumatic experiences, must be met with interventions designed to lower arousal and develop awareness and insight into the source (memory) of the fear.

Addicted survivors of trauma are used to resolving internal danger with mood altering substances. Not feeling safe is often a precursor to impulsive behavior. As noted above, Dayton (2001) discusses the phenomenon of emotional literacy. It is not necessary that a trauma survivor be fluid in their emotional literacy in order to resolve traumatic material yet they do need to be able to distinguish when they are not feeling safe. With addicts, it may be useful to develop a few words for the feelings of discontent that predispose the individual to turning to mood altering substances and behaviors. For instance, a client may not be able to articulate feelings of powerlessness or vulnerability but they may be able to distinguish an internal cue that tells them that things are “not right.” An example of this may be a commitment to tell someone when feeling “irritable” or “uncomfortable.”

3. DEVELOPMENT OF A BATTERY OF SELF-SOOTHING, GROUNDING, CONTAINMENT AND EXPRESSION STRATEGIES AND THE ABILITY TO UTILIZE THEM FOR SELF-RESCUE FROM INTRUSIONS.

Addicted survivors of trauma are accustomed to using mood altering substances and behaviors to self-soothe. The ability to use alternative methods of self-soothing is often a turning point for the survivor as they move from engulfment by the traumatic material to feeling a sense of empowerment over it.

When dealing with the traumatic material, the client must be able to identify to what extent they may explore the material before needing to retreat and return to the safety of the present. Just as with a fireman, before s/he can learn how to self-rescue, they need to be able to identify when it is warranted. One method of teaching the client how to determine this is by utilizing the Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS). This is a scale from zero to ten that indicates what level of discomfort a client is experiencing. Traumatic material will inevitably produce discomfort, but the trauma survivor must practice leaning into the resistance without being overwhelmed. With a SUDS scale, the client can identify their own limits and when self-rescue is necessary. A SUDS rating of 10 would indicate the most discomfort a survivor could imagine feeling. This may be indicated during a flashback. A SUDS rating of 0 or 1 would indicate no discomfort. By using this scale, the client is then able to gain a sense of awareness as to what extent they may safely explore the traumatic material, without becoming overwhelmed.

It is useful to ask the client to begin to narrate the traumatic experience(s) and as their emotions intensify, the clinician may challenge the client to rescue themselves from these overwhelming feelings by implementing the skills above. This successful experience can then be utilized later in treatment to empower the client to extricate him/herself from overwhelming traumatic memories. It is also a testament to the client now being empowered with choice to continue treatment and confront trauma memories.

4. POSITIVE PROGNOSIS AND CONTRACT WITH CLIENT TO ADDRESS TRAUMATIC MATERIAL.

The final important ingredient of the Safety Phase of treatment is negotiating the contract with the client to move forward to Phase II (Trauma Resolution). Remember the importance of mutual goals in the creation and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance. It is important for the clinician to harness the power of the client’s willful intention to resolve the trauma memories before moving forward. An acknowledgment of the client’s successful completion of the Safety Phase of treatment coupled with an empowering statement of positive prognosis will most likely be helpful here (i.e., “I have watched you develop some very good skills to keep yourself safe and stable in the face of these horrible memories. Judging from how well you have done this, I expect the same kind of success as we begin to work toward resolving these traumatic memories. What do you need before we begin to resolve these memories?”).

SKILLS FOR DEVELOPING, MAINTAINING & ENHANCING SAFETY

In order to fully resolve traumatic material, feelings of empowerment must mitigate the victim role. These skills are meant to be suggestive and may not work for every survivor. It is important that the client be able to identify what works for them. Some clients experience a feeling of failure if they attempt to lower their SUDS scale and it does not work. It is important that we as clinicians normalize trial and error and instill hope in the trauma survivor.

Remember that the goal of these skills is to take the client out of the fight or flight option and back into intentionality where they control their internal and external world. It is helpful to use the term staying “intentional” vs. being rendered “reactive.” When we are intentional, we have the ability to act out our intentions. When we are in a reactive state of mind, we react to situations without thought or insight. A reactive state is fear driven and impulsive.

In her excellent book, “The Body Remembers” Rothschild (2000) encourages clinicians to teach clients how to put the “brakes” on when beginning trauma therapy. She uses the analogy of teaching a new driver to be really comfortable with the braking system in a car before “accelerating”. In the same manner, she finds methods for teaching client’s how to “brake” before becoming deeply involved in trauma work. In this way, the client moderates the trauma work. A client can begin to work beyond the fear once they have learned that they need not be stuck in fear forever. Once an individual learns that they can touch just the surface of their experience and then return to a safe or neutral ground it is empowering and affords them the knowledge that they can master their own discomfort.

Progressive Relaxation

Ehrenreich (1999) provides a simple script for Progressive Relaxation that can be expanded or contracted with just a minimum of effort. Begin this exercise by instructing the individual to focus on lengthening and deepening the breath. Focus on the inhalation and exhalation making the breath smooth and deep.

Now tighten both fists, and tighten your forearms and biceps … Hold the tension for five or six seconds … Now relax the muscles. When you relax the tension, do it suddenly, as if you are turning off a light … Concentrate on the feelings of relaxation in your arms for 15 or 20 seconds … Now tense the muscles of your face and tense your jaw … Hold it for five or six seconds … now relax and concentrate on the relaxation for fifteen or twenty seconds … Now arch your back and press out your stomach as you take a deep breath … Hold it … and relax … Now tense your thighs and calves and buttocks … Hold … and now relax. Concentrate on the feelings of relaxation throughout your body, breathing slowly and deeply (Ehrenreich, 1999, Appendix B).)

Autogenics

A favorite script for Autogenic Relaxation comes from “Mastering Chronic Pain” (Jamison, 1996). Although written for a different audience, it is applicable to the addicted survivor. Autogenics is a process of using internal dialogue to self-soothe. It is NOT hypnosis. The client is in control the entire time. It begins by encouraging the client to find a relaxing place and position. Focusing on their breath allows it to soften, lengthen, and deepen. The internal dialogue can then begin.

Jamieson (1996) begins with: “Now slowly, in your mind, repeat to yourself each of the phrases I say to you. Focus on each phrase as you repeat it to yourself” (p. 73).I am beginning to feel calm and quiet. I am beginning to feel quite relaxed. My right foot feels heavy and relaxed. My left foot feels heavy and relaxed. My ankles, knees, and hips feel heavy, relaxed, and comfortable. My stomach, chest, and back feel heavy and relaxed. My neck, jaw, and forehead feel completely relaxed. All of my muscles feel comfortable and smooth. My right arm feels heavy and relaxed. My left arm feels heavy and relaxed. My right hand feels heavy and relaxed. My left hand feels heavy and relaxed. Both my hands feel heavy and relaxed. My breathing is slow and regular. I feel very quiet. My whole body is relaxed and comfortable. My heartbeat is calm and regular. I can feel warmth going down into my right hand. It is warm and relaxed. My hands are warm and heavy. It would be very difficult to raise my hands at this moment. I feel very heavy. My breathing is slow and deep. My breathing is getting deeper and deeper. I am feeling calm. My whole body is heavy, warm, and relaxed. My whole body feels very quiet and comfortable. My mind is still, calm, and cool. My body is warm and relaxed. My breathing is deeper and deeper. I feel secure and still. I am completely at ease. I feel an inner peace. I am breathing more and more deeply (Jamieson, 1999, p.73-74). |

| Now encourage the client to bring their attention back into the room in which they are relaxing. Suggest that they can bring feelings of relaxation into their regular waking day simply by focusing in the same manner as they have during this exercise.It can be very empowering for the client to develop their own script which they can then read when they are feeling overwhelmed or in need of self-rescue. This can also assist the client in becoming more creative and proactive in resolving their traumatic material.Diaphragmatic BreathingIf we watch an infant sleep, we will see the rhythmical movement of deep belly breathing. This is the ideal breathing for relaxation and the nourishing of the body with the breath. Again, it is important for the addicted survivor to recognize when they are in need of an exercise to self-soothe. For instance, many addicted survivors can relate feelings of anxiety to a “lump in their throat” or a “pain in their chest.” These somatic experiences will act as a cue that feelings of safety may need to be addressed.When we feel upset or anxious about something our breathing is often the first thing to change. It is likely to become shallow, rapid and jagged or raspy. If on the other hand, we were to practice an intentional diaphragmatic breathing, we would be more able to consciously regulate our breathing when we became upset.Find a comfortable, unrestricting position to sit or lie in. Place your hands on your belly as a guide to the breath. Begin to consciously slow and smooth out the breath. Just noticing the rhythm of the breath through the inhalation and exhalation. Is it smooth, deep and full or jagged, shallow and slight? Now focus on bringing a deeper breath into the belly. Let a full breath be released on the exhalation. Inhale fully, not holding the breath at any time. On the exhalation release completely and pause, counting to 3 after the exhalation is complete. Then inhale slow full and deep. Continue to focus in this manner on the breath.Gentry (2002), suggests placing one’s clasped hands behind the neck. This opens the chest through the lifting and spreading of the elbows. As this occurs, breath moves much more freely deep into the belly, thus allowing an excellent alternative (to hands on the belly) for those just learning deep breathing exercises.At first, the individual is taught to deep breath in sets of 5. Then this is increased to 10 inhalations and exhalations. Finally, an instruction is given to practice 2 times each day for 5 minutes per day. In this way, the individual is learning to relax through deep breathing.3-2-1 Sensory Grounding & ContainmentThis technique assists the trauma survivor in developing the capacity to “self-rescue” from the obsessive, hypnotic and numinous power of the traumatic intrusions/flashbacks. It is based on the assumption that if the survivor is able to break his/her absorbed internal attention on the traumatic images, thoughts and feelings by instead focusing on and connecting with their current external surroundings through their senses (here-and-now), the accompanying fight/flight arousal will diminish. This technique will assist the survivor in understanding that they are perfectly safe in their present context and the value of using their sensory skills (sight, touch, smell, hearing, and even taste) to “ground” them to this safety in the present empirical reality. | ||||||||

| Begin by asking the client to tell part of their trauma narrative and allow them to begin to experience some affect (reddening of eyes, psychomotor agitation, constricted posture).When they have begun to experience some affect (~ 5 on a SUDS Scale), ask them “would you like some help out of those uncomfortable images, thoughts and feelings?If they answer “yes,” ask them to describe, out loud, three (3) objects that they can see in the room that are above eye level. (Make certain that these are physical, not imaginal, objects).Ask them to identify, out loud, three (3) “real world” sounds that they can currently hear sitting in the room (the sound can be beyond the room, just make certain that they are empirical and not from the traumatic material).Hand them any item (a pen, notebook, Kleenex), and ask them to really feel it and to describe, out loud, the texture of this object. Repeat this with two additional objects.client, ask them to reach out, touch, and describe the texture of two objects). Repeat this now with one object each for sight, sound, and texture.When completed, ask the client “What happened with the traumatic material?” Most of the time your client will describe a significant lessening of negative feelings, thoughts and images associated with the traumatic material. | ||||||||

| Postural GroundingPostural grounding is a technique drawn from practice with clients who have dissociative symptoms. As a trauma survivor begins to experience the images and feelings associated with a flashback, they can often be observed to migrate into a constricted and fetal posture of protection. In addition, the clinician can usually notice psychomotor agitation in the form of shaking legs, tremors, either fixated or scanning eyes, and shallow breathing.When the client begins exhibiting these signs of re-experiencing and arousal, ask them “Would you like some help in getting out of there [those images and feeling]?” If the client says, “yes,” follow the script below to help them develop the capacity for self-rescue from flashbacks. | ||||||||

| While the client is exhibiting the constricted and fetal posture, ask her/him, “How vulnerable to do feel right now in that posture?” You will usually get an answer like “very.”Ask them to exaggerate this posture of constriction and protection (becoming more fetal) and then to take a moment to really experience and memorize the feelings currently in the muscles of their body.Next, ask them to, “stand up, and turn around and then to sit back down with an ADULT POSTURE-ONE THAT FEELS’ IN CONTROL.” [It is helpful for the clinician to do this with the client as demonstration].Ask them to exaggerate this posture of being IN CONTROL and to now really notice and memorize the feeling in the muscles of their body.Ask them to articulate the difference between the two postures.Ask them to shift several times between the two postures and to notice the different feelings, thoughts, and images associated with the two opposite postures.Indicate to the client that they are now able to utilize this technique anytime that they feel overwhelmed by posttraumatic symptoms-especially in public places.Discuss with the client opportunities where they will be able to practice this technique and make plans with them for its utility. | ||||||||

Anchoring: Safety

This exercise is an anchoring process that enables the individual to gain access to a safety state without the use of “hypnosis” type exercises.

1) Identify resource (e.g., safety, courage, fear)

2) Identify historical experience where resource was present

a) “Describe context” (i.e., at the cottage with the fireplace warming the room)

b) Find the exact second that the place, time, objects, people present, etc.

c) “Close eyes and re-experience” (10 – 15 seconds)

3) Clinician makes note resource/problem state was most intense

4) Behavioral

a) “Close your eyes and imaging you are watching a videotape of this moment…”

b) “What would we see you doing…specifically?”

c) “What would be the look on your face?”

d) Make note

5) Cognitive

a) “Imagine that there is a tiny microphone that can listen to your thoughts

at this moment…”

b) “What would we hear your mind say at the moment of _____ (resource)

is the strongest?”

c) Make note

6) Affective/Sensory

a) “At the moment that _________ is the strongest…”

b) “What do you feel in your body?”

c) “What sensations do you experience?”

7) Establish Anchor

a) “Close your eyes and begin to experience ___________about 15 seconds

before it reaches its ‘peak intensity.”

b) Clinician narrates context

c) Clinician narrates behavioral

d) Clinician narrates cognitive

e) Clinician narrates affect/sensory

f) “Allow this experiences of ____________ (resource state) to intensify even

more…feel it expanding in your chest…in your mind…”

8) Trigger

a) Now, squeeze together the thumb and forefinger of your dominant hand

(5 seconds)…put all of the ___________ into that squeeze.”

9) Back to normal consciousness

a) Test trigger (“How much of that feeling comes back when you squeeze your

thumb and forefinger together now?”) ____%

Safe Place Visualization

The next exercise, although NOT hypnosis is a technique that does utilize some elements that are like “hypnotherapy”. It is therefore limited for use by those who have had formal training and appropriate educational background to offer that type of work.

This next exercise is adapted from the Treatment Manual for Accelerated Recovery from Compassion Fatigue (Gentry & Baranowsky, 1999).

Pre-visualization information

Find a place and position where you can relax. This should be a place where you can be assured of minimal interruptions. Take the time to set the space for your maximum benefit. Once you are satisfied with the environment and feel it will be one that is safe and relaxing we will be ready to begin.

During this exercise you will have the opportunity to enjoy a sense of deep relaxation through a guided exercise. Through the exercise you will be instructed in the inner imagining of a Safe Place that may be a place you have been to before or one entirely made up in your imagination.

It is important to remember that this is NOT hypnosis but instead a guided relaxation and imagery exercise in which you are in control while being deeply relaxed. You CAN stop at any time if you need to BUT we recommend that you experience the entire exercise without interruptions to enjoy the greatest benefit and insight.

| Focus on the sense of relaxation now in the muscles in the back of your eyes and notice how this relaxation can spread. Now as your eyelids softly rest over your eyes notice how you are able to soften your facial muscles — first those that are closest to your eyes but then more and more as you sense a smoothing, soothing, warming sensation spread across your face. Notice this warming, soothing sensation spread greatly across your forehead — across your eyes — through your hairline. Notice as it warms and softens the lines of your face. Just notice and let the gentle warmth calm your face. This calming sensation moves down your face … your nose … lips … chin … until your whole face becomes a numb mast of relaxation. Even the mind takes on a soothing a mellow position … until the mind feels very quiet. Listen to the sound of my voice and any other sounds without doing anything. Let these sounds be signals to let you know that you are safe, here in this room. Allowing you now to pay even closer attention to the INSIDE world. Simply let the sounds assure you that you are in a safe place in this room. Feeling that safety allow yourself to relax and slowly let the soothing warmth spread through to your neck muscles helping you to release any tensions. The warmth now moves down through your arms all the way to your fingertips. As it does you can release tension in your upper body by imagining it spilling out through the tips of your fingers and into the ground below. Allow the warmth to spread through to your chest and fill up your lungs … relaxing your muscles, relaxing your stomach, softening the muscles of the back and warming and releasing any tensions there. Continue to pay attention to my voice. Notice any points of tension and bring the soothing warmth to those points so they too can soften and relax. Bring the warmth through to your lower back, thigh, calves, feet, and toes. Become aware now that you can release even more tension from your lower body by imagining it spilling down through all the way to the tips of your toes and spilling out and into the ground. Just let your body relax as deeply as it wants letting your conscious mind stray where it might … and while your body relaxes it brings a feeling of calm detachment … and a feeling that time doesn’t matter, time is not important … you feel calm and emotionally detached.Safe Place ImageryNow allow your mind to find a relaxed and soothing space — a safe place. This is a place from the past that you have been to before or one from your imagination. Either way is OK, because it all belongs to you. Begin to develop a picture as a Polaroid film would develop. Watch as the safe place develops exposing itself to you. Notice how the lights, colors, textures, that surround you are now soothing to you. Notice what is above and below you. Walk around this place taking notice of all the sounds of relaxation … those that are close and those sounds that are far away. Notice the soothing fragrances in this safe place … those that are distinct and those that seem subtle. Be aware of all the safe fragrances. Now notice the temperature and quality of the air…reach out and touch some of the objects in this place of safety…notice all the textures. Be aware that anything that is safe can be imported into this place by you. If anything seems unsafe or threatening, allow yourself to send it out and notice how you are able to do this. Feel and appreciate all the relaxing sounds … assuring smells… and the sight of safety … feel it, appreciate it. Take it all in and memorize it so that if someone asked you to draw it at a later date you could do this in great detail … or can call it up at any time (5-10 seconds of silence). Also notice how you can begin to move about…moving about with the feeling of relaxed joyfulness … relaxed joyfulness …this is our natural state. Remember what it feels like to be relaxed…and joyful. Take a moment now to give yourself permission…full permission to enjoy this state of comfort…of relaxation…of peace (be silent for about 10 seconds).Slowly begin to bring your awareness back into this room realizing that shortly but not just yet you will open your eyes. Before you do this realize that you will feel more relaxed and better able to get on with the rest of your day. Make small movements in your fingers and toes … make small movements in your arms and legs. Whenever you are ready slowly begin to bring your awareness fully into this room – opening your eyes when you are ready. | |||||||

| Flashback JournalThe following journal format is useful as a functional analysis of triggers and symptoms. It allows the survivor to chart their progress and identify some of the most effective ways of coping. Thoughts of using and impulses can also be included in this journal. | |||||||

Flashback Journal

| Symptom | Trigger | Memory | SUDS | Self-soothing Skill(s) used | SUDS |

Rituals

Ritualistic methods for safety and stabilization can vary widely. The key is to create a form of practice or ceremony that reinforces the individual’s sense of reassurance, safety or security. One lovely ritual is to have a “marriage” ceremony with oneself. This effectively strengthens the internal tie – the person is now responsible for themselves and fully empowered to act on their best behalf. If things are not going well or goals have been set, they must look to themselves to move their lives forward in the direction that is desired. This takes an act of will but it is much more likely that one will achieve ones greatest hopes and dreams if we take full responsibility for these dreams. After all, who else is as fully informed of what we truly wish from life if not ourselves.

The ceremony is to be orchestrated in the vision of the individual. This can be completed alone or in the company of trusted counselors or friends/family. In one example, the individual chose to complete the ritual alone. Candles were lit, paint and paper was available for creative expression, a colorful silk robe was worn and meaningful music was played. The individual wrote their wishes for the future and their commitment to themselves. They wrote a “self-marriage” ceremony in which they made a strong and earnest vow to “care for themselves in a manner that met their inner desires, hope and dreams”. In effect, this ceremony was a joyous occasion one of personal commitment to future and self-support. The individual came to the conclusion that if they treated themselves in this manner they would have nothing to feel disappointed about and if they did not they would have no one to “blame” other than themselves.

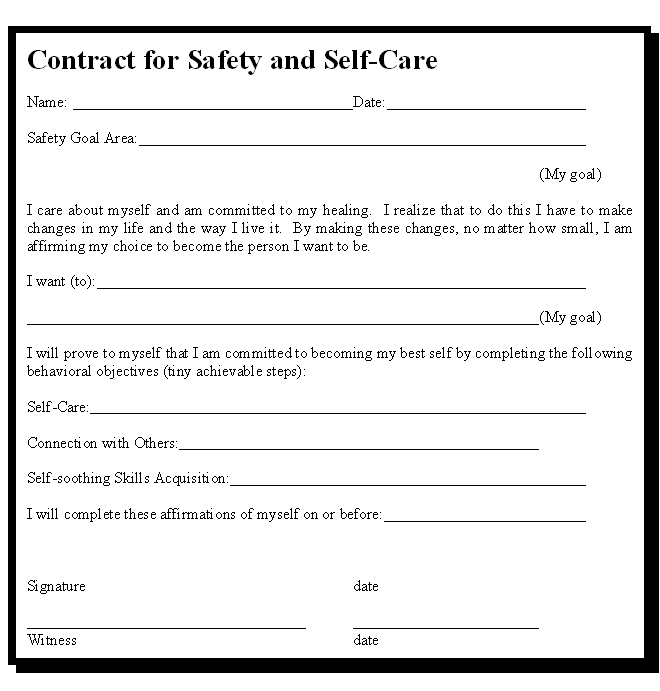

Another approach is to make a concrete commitment or contract in writing to move toward healing. This can serve as a mantra for the client as s/he makes a commitment to healing and moving through her the part of the self that has been holding him/her back. Some of these commitments take place as affirmations, songs, mission statements, and the like. Again, this is an opportunity for the client to become creative in her/his healing process.

Below is an example of a commitment contract. The contract may be used between clinical sessions or by the survivor independently. By operationally defining what their goals are, their progress can be easily identified and they begin to recognize their own capacity for healing.

Buddha’s Trick

This is an awareness technique to assist clients by improving their understanding of the necessity for processing time and the level of energy required for suppression. Many people who have been exposed to traumatic events attempt to “push bad thoughts out of their minds.” It is also not uncommon for addicted survivors to have thoughts of using while in early, or even late recovery. Again, the thoughts are met with judgement and feelings of inferiority or failure. In significant numbers, this approach tends to result in the unfortunate outcome of post-trauma symptoms (i.e., intrusive thoughts, poor sleep, anxious feelings, avoidance). By refusing to think about difficult events we fail to establish a complete narrative, make sense of our experiences, desensitize through exposure and recognize that we are now safe. Baer (2001) provides an excellent illustration of this technique in his publication the Imp of the Mind (p. 95-99).

When we are feeling very badly about something that has occurred or that we worry might occur, we sometimes make a big effort to “suppress” our thoughts, feelings, memories associated with the disturbing recollection. Many research studies show that this type of thought suppression does not work. In addition, it uses a lot of energy to keep thoughts out of our mind and is therefore exhausting. It also increases the fear factor – as we are hiding this thing from our thoughts, reducing our ability to review and resolve our feelings and thus making it seem even more unbearable than it is. Recall someone saying to you that something terrible has happened and then not telling you right away what it is … your mind arrives at a conclusion that is even worse than the actual reality, in most cases.

Thought Exercise

Instruct the individual to think of a “Stone Buddha” for 1 minute keeping their mind as focused as possible during this time. If at any time, they lose their focus they are to lift a finger alerting both themselves and you that they have lost their focus. Now discuss what this exercise was like, what they observed and how much energy it took to keep their mind focused.

Next, the individual is instructed to keep “Stone Buddha’s” out of their mind for a full minute. Again, they are to lift a finger every time “Stone Buddha” comes into the mind. When the minute is over they are given time to reflect on the difficulty of this exercise and the amount of energy it takes to keep the mind focused.

Now they are asked to notice if “Stone Buddha’s” come to mind at an even greater rate than prior to thought suppression. This is called the rebound effect and is noted in a number of research studies. The studies show that the object of suppression surfaces more often and more vigorously than prior to suppression.

Explain this phenomenon to the individual so they understand the importance of reflection and resolution as opposed to the tendency to want to suppress our negative thoughts, feelings, memories or fears.

This is an extremely useful approach when preparing the individual for trauma review and reducing treatment resistance as the individual begins to recognize that suppression does not work efficiently and is likely the reason for ongoing feelings of distress. This exercise is also a practical clarification as to why “Thought Stopping” is frequently unsatisfying for individuals seeking relief from trauma-related thoughts.

Centering

This exercise springs from the increasingly familiar work on “mindfulness” or reflection and acceptance. Or as Jon Kabat-Zinn (1990) explains in his grounded breaking book Full Catastrophe Living, “Mindfulness is cultivated by assuming the stance of an impartial witness to your own experience” (p.33). He goes on to state that as we begin to pay attention to the internal dialogue “it is common to discover and to be surprised by the fact that we are constantly generating judgments about our experience” (p. 33).

The next important piece of mindfulness is “acceptance”. Without this we will make no progress, as we cannot live peacefully within our own bodies if we are unable to gracefully accept its natural fragility along with its strength. If we are plagued with chronic headaches following a traumatic event we will certainly be worse off if we grow angry and frustrated every time we have a headache. Our anger and frustration will fuel our headache feeding it into a much worse bodily felt experience.

Thich Nhat Hanh (1990) explains a five-step process for centering that opens a dialogue between the individual and their own internal bodily felt experiences. He recommends that we allow ourselves to get to know and reflect on our internal processes whether it is fear, pain, sadness, confusion, irritation, etc. The first step is to just notice what comes up leaving judgment aside.

The second step is to greet the internal experience (i.e., Hello sadness. What is happening with you today? Why are you here?). This is in contrast to the common response which may be “hey, get out of here sadness, you have no place inside of me, who invited you!” In this way we are no longer battling with ourselves. It becomes acceptable to for us to feel whatever surfaces. The mindfulness is present and can moderate our internal experience of sadness – we are to just watch and let our attachment to judgment drop. Conscious breathing is an integral component to centering.

In the third step, you coax an inner calmness just as you would soothe a young child who is feeling sadness or pain. You might say, “I am here sadness and I will not abandon you. I am breathing into my sadness with calm cooling breath.” Being one with the feeling allows it the space and time to be nurtured, explored, expressed, acknowledged and provides the opportunity for respectful recovery.

The fourth step begins the process of releasing the feeling. You have faced the fearful emotion living in your body. It is now time to recognize that as you add a calm mindfulness the sadness begins to transform. You have taught your body to feel ease even in the presence of deep sadness. You have sent a new message to your body – that you are ready to remain present and care for yourself even when faced with disturbing internal messages. Make a conscious decision to soften the feeling even more noticing that it can become a gentler expression. Imagine yourself smiling calmly at your feeling and letting it go with willingness to release.

The fifth step involves a deeper look. Bring your mindfulness to the source of the discomfort. Even if it has fully dissipated, the body will have a memory of its existence. Ask, “What is this feeling about? Where did it come from? What internal or external causes form this experience?” With questions like this, we can better understand ourselves. With understanding we can find the source of our internal distress. We can offer our own wise counsel, offering words of kindness and support, self-acceptance and transformation.

This self-directed exercise can add to the richness of anyone’s life. The ability to be compassionate and patient with one’s self when learning these techniques is helpful. The key to mastering these techniques is practice and self-acceptance. Lingering feelings of distress may be met as continued invitations for practice and growth vs. signs that you are not getting any better or that the self-soothing techniques are not working.

CLOSURE

Previously, this article introduced two individuals, Brad and Erica, both struggling with trauma and addiction. For individuals confronting the dual challenge of trauma and addiction, there is an even greater need for the ability to develop a feeling of safety. Trauma-related triggers for the addictive behaviors are often not identified until after the behavior occurs and the damage is done. For Brad and Erica, an awareness of how their desire or compulsion to use substances to cope was connected to past trauma may have enabled them to find alternative ways of coping. With greater understanding and more resources for coping at their disposal, each may have been able to respond with healthier means of self-regulation. Based on a foundation of safety and stabilization, traumatic material can be resolved and the continuation of self-destructive behaviors will gradually dissipate.

With the ability to self-regulate anxiety, impulsive behavior and traumatic material can be mastered and addicted survivors can move to the next phase of trauma resolution. However, without a strong foundation of safety, addicted survivors often resort to old patterns of coping and self-soothing, i.e., addiction–as these behaviors were at one time a means of survival. By offering new coping strategies, addicted survivors of trauma can learn to live life without the use of mood altering substances or behaviors and still manage the traumatic symptoms that may resurface in their absence.

Treating the addicted survivor of trauma can be debilitating for the clinician as well as the system that provides this treatment. Individuals with co-occurring unresolved trauma and addiction tend to have more conflicts and act out more often when attempting to address the trauma or to maintain abstinence. Without an understanding of how trauma and addiction are interrelated and an integrated treatment approach, the cycle of retraumatization and relapse will likely continue. For an optimal outcome when treating addicted survivors of trauma, it is essential that treatment begin with a strong foundation of safety. With this foundation solidly in place, the chances of a sustained recovery increases and the individual can lead life free from traumatic memories and addiction–TraumAddition become recovery.

J. Eric Gentry is a Licensed Mental Health Counselor in the state of Florida and holds a Master’s Degree in Counseling and a Certificate of Advanced Study in Psychotraumatology from West Virginia University. Eric is Director of Training of Corporate Crisis Management Inc.-a company specializing in assisting businesses and organizations to prepare for and manage a crisis or traumatic event through education, training and on-site incident management. He is the owner of Compassion Unlimited, a private psychotherapy, training, and consulting practice. He is the co-author of the soon to be published book “Tools for Trauma: A CBT Approach.”